Amish

| Amish |

|---|

|

| Total population |

| 350,000 (2021 est. for U.S.) |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States, Canada |

| Languages |

| Pennsylvania Dutch, Alemannic German, English |

| Religions |

| Anabaptist |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Germans, Swiss German, Pennsylvania Dutch |

The Amish (Amisch or Amische) (IPA: ˈɑːmɪʃ) are an Anabaptist Christian denomination in the United States and Canada (Ontario and Manitoba) known for their plain dress and avoidance of modern conveniences such as cars, zippers and electricity. The Amish separate themselves from mainstream society for religious reasons. They do not join the military, apply for Social Security benefits, take out insurance, or accept any form of financial assistance from the government.

Most speak a German dialect known as Pennsylvania Dutch at home and in church services, and learn English in school. The Amish are divided into separate fellowships consisting of geographical districts or congregations. Each district is fully independent and has its own ordnung, or set of unwritten rules.

The Old Order Amish provide the concept that most outsiders have when they think of the "Amish." The Old Order Amish are distinguished from the more moderate Beachy Amish and New Order Amish by their strict adherence to the use of horses for farming and transportation, their traditional manner of dress, and their refusal to allow electricity or telephones in their homes.

Population and distribution

The geographic and social isolation of Amish communities makes it difficult to determine their exact total population. In 2021, over 350,000 Old Order Amish lived in the United States,[1] and about 6,000 lived in Canada. The population grows rapidly as the Amish generally do not use birth control.[2] This number, however, includes young people who have yet to be baptized.

There are Old Order communities in 31 states, with the largest populations in three states: Pennsylvania (84,100), Ohio (80,240), and Indiana (60,960). The largest Amish settlements are in Holmes County, Ohio, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania and LaGrange, Indiana. With an average of seven children per family, the Amish population is growing rapidly, and new settlements are constantly being formed to obtain sufficient farmland. Other notable Amish communities are located in Kent County, Delaware and Montgomery County, New York. Some Beachy Amish have relocated to Central America, including a sizable community near San Ignacio, Belize.

Most Old Order and conservative Amish groups do not proselytize, and conversion to the Amish faith is rare. The Beachy Amish, on the other hand, do pursue missionary work.

Amish as an ethnic group

The large majority of Amish are united by a common Swiss-German ancestry, language, and culture, and they marry within the Amish community. They therefore meet the sociological criteria of an ethnic group. However, the Amish themselves generally use the term "Amish" only to refer to accepted members of their church community, and not as an ethnic designation. Those born into the group who do not choose to join the church and live an Amish lifestyle are no longer considered Amish, just as those who live the plain lifestyle but are not baptized into the Amish Church are not Amish. Certain Mennonite churches were formerly Amish congregations. Although more Amish immigrated to America in the nineteenth century than during the eighteenth century, most Amish today descend from eighteenth century immigrants, as the Amish immigrants of the nineteenth century were more liberal and most of their communities eventually lost their Amish identity. [3]

History

The Amish movement takes its name from that of Jacob Amman (c. 1656 – c. 1730), a Swiss-German Mennonite leader. Amman believed the Mennonites were drifting away from the teachings of Menno Simons and the 1632 Mennonite Dordrecht Confession of Faith, particularly the practice of shunning (known as "the ban" or Meidung). Amman insisted upon this practice, even to the point of expecting a spouse to refuse to sleep or eat with the banned member until he/she repented of his/her behavior. This strict attitude brought about a division in the Swiss Mennonite movement in 1693 and led to the establishment of the Amish.

The Amish first began migrating to the colony of Pennsylvania in the eighteenth century, where William Penn had declared freedom of religion, and welcomed immigrants from Europe to settle. They were part of a larger migration from the Rhineland-Palatinate and neighboring areas in Germany. They came, along with their non-Anabaptist neighbors, largely to avoid religious wars and poverty, but also to escape religious persecution. The first immigrants went to Berks County, Pennsylvania, but later moved, motivated both by land issues and by security concerns tied to the French and Indian War. Many eventually settled in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Amish congregations that remained in Europe slowly merged with the Mennonites.

Origins of the Old Order

No Old Order movement developed in Europe, and thus all Old Order communities are located in the Americas. In fact, most Amish communities that were established in North America did not ultimately retain their Amish identity.

In the 1860s ministerial conferences were held in Wayne County, Ohio, concerning how the Amish should deal with the pressures of modern society. The meetings themselves were an innovation, for the notion that bishops should get together to work for uniformity was unprecedented in the Amish tradition. However, after several meetings, the conservative bishops decided to boycott the conferences. Within a few decades, the more progressive Amish became Amish Mennonites, and were later absorbed into the Old Mennonites (not to be confused with Old Order Mennonites). The remaining smaller faction became the Old Order Amish of today.

Religious Practices and Lifestyle

The Old Order Amish do not have churches, but hold their prayer services in private homes. Thus they are sometimes called "House Amish."

Amish lifestyle is dictated by the Ordnung (German, meaning: order), which differs slightly from community to community. Groups may disagree and even separate over minor matters such as the width of a hat-brim, the color of buggies, as well as larger issues such as the use of automobiles, electricity, or telephones. The use of tobacco (excluding cigarettes, which are "worldly")[4] and moderate use of alcohol[5] are generally permitted, particularly among older and more conservative groups.

Hochmut and Demut

Two key concepts for understanding Amish practices are their rejection of Hochmut (pride, arrogance, haughtiness) and the high value placed on Demut or "humility" and Gelassenheit (calmness, composure, placidity) — often translated as "submission" or "letting-be."

The willingness to submit to the will of God, as expressed through group norms, is at odds with the individualism central to the wider American culture. The Amish anti-individualist orientation is the motive for its rejecting labor-saving technologies that might make one less dependent on community or which might start a competition for status-goods or cultivate individual or family vanity. It is also related to the Amish tradition of rejecting education beyond the eighth grade, especially speculative study that has little practical use for farm life but may awaken personal and materialistic ambitions.

Separation from the outside world

The Amish often cite three Bible verses that encapsulate their cultural attitudes:

- "Be not yoked with unbelievers. For what do righteousness and wickedness have in common? Or what fellowship can light have with darkness?" (2 Corinthians 6:14)

- "Come out from among them and be ye separate, saith the Lord." (2 Corinthians 6:17)

- “And be ye not conformed to this world, but be ye transformed by the renewing of your mind that ye may prove what is good, and acceptable, and perfect, will of God.” (Romans 12:2)

The Amish prefer to work at home, both out of concern for the effect of a parent's absence on family life, and in order to minimize contact with "English" (originally referring to anyone not of German descent). However, increased prices for farmland and decreasing revenues for low-tech farming have forced many Amish to work away from the farm, particularly in construction and factory-labor. In those areas where there is a significant tourist trade, they also engage in shop work and crafts aimed for the tourist market. The decorative arts play little role in authentic Amish life, although the prized Amish quilts are a genuine cultural inheritance.

Amish lifestyles vary between (and sometimes within) communities. These differences range from profound to minuscule. Beachy Amish—also called Amish Mennonites—drive black automobiles, while in some communities various groups differ over the number of suspenders males should wear, how many pleats there should be in a bonnet, or if one should wear a bonnet at all. Groups with similar policies are held to be "in fellowship" and consider each other members of the same Christian church. Groups in fellowship can intermarry and have communion with one another, an important consideration for avoiding problems that may result from genetically closed populations. Thus minor disagreements within communities over dairy equipment or telephones in workshops can create splinter churches and divide multiple communities.

Some of the strictest Old Order Amish groups are the Nebraska Amish (White-top Amish), the Troyer Amish, the Swartzendruber Amish. Nearly all Old Order groups, speak the Amish Deitsch dialect in the home, while more progressive Beachy Amish groups often use English in the home.

Baptism, Rumspringa, and shunning

The Amish and other Anabaptists do not believe that a child can be meaningfully baptized, and it was their insistence on adult baptism that caused the Anabaptists to be persecuted in Europe. Amish children are expected to follow the will of their parents in all issues, but when they come of age, they must decide for themselves whether to make an adult, permanent commitment to the church.

Rumspringa ("running or jumping around") is the general term for adolescence, during which rules may be relaxed and some misbehavior tolerated. At the end of this period, Amish young adults are expected to find a spouse and be baptized. Statistics indicate that approximately half of the adolescents in the larger Amish communities and the majority in smaller communities remain within the norms of Amish dress or behavior during Rumspringa. Thus, many diverge from custom during this period. For most, this is just a tentative foray—a trip to the local movie theater, driving lessons, or a few dates with a non-Amish partner. However, for some Amish youth Rumspringa is all about sex, parties, and loud music.[6] Overall, the majority of Amish youth ultimately choose to join the church; the proportion simply varies from community to community.

Some Amish communities will actively shun those who decide to leave the church after having been baptized, even who associate with an Amish congregation with different doctrines. However, in other cases, those young people who leave the church prior to being baptized are not shunned, and may maintain close contact with their families. Still other communities practice hardly any shunning, keeping close family and social contact with those who leave the church, even after baptism.

The Swartzendruber Amish split from the wider Amish community because they felt that shunning was not being applied strictly enough. Shunning is also sometimes imposed by bishops on church members guilty of offenses such as using forbidden technology.

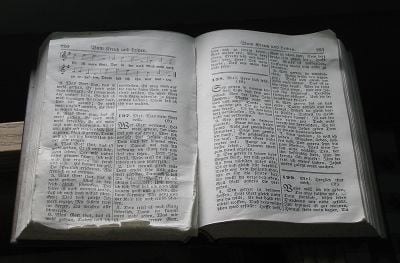

Religious services

The Old Order Amish have worship services every other Sunday at private homes where they are often seated in several different rooms, men separate from women. Worship begins with a short sermon by one of several preachers or the bishop of the church district, followed by scripture reading and silent prayer, and another, longer sermon. The service is interspersed with hymns, sung without instrumental accompaniment or harmony. Singing is usually very slow, and a single hymn may take 15 minutes to finish. Worship is followed by lunch and socializing. The service and all hymns and scriptures are in Deitsch. Amish preachers and deacons are selected by lot (based on Acts 1:23–26) from a group of men nominated by the congregation. They serve for life and have no formal training. Amish bishops are similarly chosen by lot from those selected as preachers.

Communion

Generally, the Amish hold communion in the spring and the autumn, and not necessarily during regular church services. As with regular services, the men and women sit in separate rooms. The ritual ends with members washing and drying each other's feet.

Baptism

The Amish practice of adult baptism is part of the admission into the church. Admission is taken seriously; those who choose not to join the Church can usually still visit their friends and family, but those who leave the church after being baptized are normally shunned by the entire community. Those who are about to be baptized sit with one hand over their face, to represent their submission and humility to God and the church. Typically, a deacon will ladle water from a bucket into the bishop's hand, and the bishop will sprinkle the head three times, in the name of Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, after which he blesses each new male member of the church and greets each into the fellowship of the church with a holy kiss. His wife similarly blesses and greets each new female church member.

Weddings

Weddings are typically held on Thursdays in late autumn, after the harvest is in. The bride wears a new blue linen dress that will be worn again on other formal occasions. She wears no makeup, and will not receive an engagement or wedding ring because the Ordnung prohibits personal jewelry. The marriage ceremony itself may take several hours, followed by a community reception that includes a banquet, singing and storytelling. Newlyweds spend the wedding night at the home of the bride's parents. Celery is one of the symbolic foods served at Amish weddings. Celery is also placed in vases and used to decorate the house instead of flowers. [7]

Funerals

Funeral customs appear to vary more from community to community than other religious services. In Allen County, Indiana, for example, the Amish engage Hockemeyer Funeral Home, the only local funeral director who offers a horse-drawn hearse and embalms the body. The Amish hold funeral services in the home, however, rather than using the funeral parlor. Instead of referring to the deceased with stories of his life, eulogizing him, services tend to focus on the creation story and biblical accounts of resurrection. After the funeral, the hearse carries the casket to the cemetery for a reading from the Bible; perhaps a hymn is read (rather than sung) and the Lord's Prayer is recited. The Amish usually, but not always, choose Amish cemeteries, and purchase gravestones which are uniform, modest, and plain; in recent years, they have been inscribed in English. After a funeral, the community gathers together to share a meal.

Modern technology

The Amish, especially those of the Old Order, are probably most known for their avoidance of certain modern technologies. The Amish do not view technology as evil, however; and individuals may petition for acceptance of a particular technology in the local community. In some communities, the church leaders meet annually to review such proposals. In others, it is done whenever necessary.

Electricity, for instance, is viewed as a connection to, and reliance on, "the World," which is contrary to the doctrine of separation. The use of electricity also could lead to the use of household appliances such as televisions, which would compromise the Amish tradition of a simple life and introduce individualist competition for worldly goods that would be destructive of community.

In certain Amish groups, however, electricity can be used in very specific situations. For example, if electricity may be used if it can be produced without access to outside power lines. Twelve-volt batteries are acceptable to these groups. Some Amish will also hire drivers for visiting family, monthly grocery shopping, or commuting to the workplace off the farm—although this too is subject to local regulation and variation.

The Amish normally avoid using the telephone because it, like electricity, interferes with the principle of separation. However, some Amish—including many in Lancaster County—do use the telephone, primarily for important outgoing calls, with the added restriction that the telephone not be inside the home, but rather in a phone "booth" placed far enough from the house as to make its use inconvenient. Commonly these private phone shanties are shared by more than one family, fostering a sense of community. Today, some Amish, particularly those who run businesses, use voice mail service.[8] Amish families without phones will also use trusted "English" neighbors as contact points for passing on family emergency messages. Some New Order Amish will use cellphones and pagers, but most Old Order Amish will not.[9]

Language

In addition to English, most Amish speak a distinctive High German dialect called Pennsylvania German or Pennsylvania Dutch, which the Amish themselves call Deitsch ("German"). Although now limited primarily to the Amish and Old Order Mennonites, Pennsylvania Dutch was once spoken by many German-American immigrants in Pennsylvania, especially by those who came prior to 1800. The so-called Swiss Amish speak an Alemannic German dialect that they call "Swiss." Beachy Amish, especially those who were born roughly after 1960, tend to speak predominantly in English at home. All other Amish groups use either Pennsylvania German or "Swiss" German as their in-group language of discourse. There are small dialectal variations between communities. The Amish themselves are aware of regional variation, and occasionally experience difficulty in understanding speakers from outside their own area.

Deitsch is distinct from Plautdietsch and Hutterite German dialects spoken by other Anabaptist groups.

Dress

The dress code for some groups includes prohibitions against buttons and zippers, allowing only hooks and eyes to keep clothing closed; others may allow small undecorated buttons in a dark color. In some groups, certain articles can have buttons and others cannot. The restriction on buttons is attributed in part to their association with military uniforms, and also to their potential for serving as opportunities for vain display. Straight-pins are often used to hold articles of clothing together. In all things, the aesthetic value is "plainness": clothing should not call attention to the wearer by cut, color or any other feature. Prints such as florals, stripes, polka-dots, etc. are not allowed in Amish dress.

Women wear calf-length plain-cut dresses in a solid color such as blue. Aprons are often worn—usually in white or black—at home and always worn when attending church. A cape which consists of a triangular shape of cloth is usually worn beginning around the teenage years and pinned into the apron. In the colder months, a long woolen cloak is added.

Heavy bonnets are worn over the prayer coverings when Amish women are out and about in cold weather, with the exception of the Nebraska Amish who do not wear bonnets.

Men typically wear dark-colored trousers and a dark vest or coat, suspenders (Brit. braces), broad-rimmed straw hats in the warmer months and black felt hats in the colder months. Single Amish men are clean-shaven, and married men grow a beard. In some more traditional communities an unmarried man will grow a beard after he is baptized. Moustaches are not allowed, because they are associated with the military and give opportunity for vanity.

During summer months, the majority of Amish children go barefoot, including to school. The prevalence of the practice is attested in the Pennsylvania Deitsch saying, "Deel Leit laafe baarfiessich rum un die annre hen ken Schuh." (Some people walk around barefooted, and the rest have no shoes.) The amount of time spent barefoot varies, but most children and adults go barefoot whenever possible.

Health issues

The Amish are distinguished by the highest incidence of twinning in a known human population, as well as various metabolic disorders and unusual distribution of blood-types. Since almost all of the current Amish descend primarily from about 200 founders in the eighteenth century, some genetic disorders from a degree of in-breeding exist in more isolated districts. However, Amish do not represent a single closed community, but rather a collection of different demes or genetically closed communities.[4] Some Amish are afflicted by inheritable genetic disorders, including dwarfism (Ellis-van Creveld syndrome). Some of these disorders are quite rare, or even unique, and serious enough that they increase the mortality rate among Amish children. The majority of the Amish accept these as "Gottes Wille" (God's will) and reject any use of genetic tests prior to marriage to prevent the occurrence of these disorders and also refuse genetic tests to the fetus to discover if it has any genetic disorder.

A handful of American hospitals, starting in the mid 1990s, created special outreach programs to assist the Amish. Treating genetic problems is the mission of Dr. Holmes Morton's Clinic for Special Children in Strasburg, Pennsylvania, which has developed effective treatment for such problems as maple syrup urine disease, which previously was fatal. The clinic has been enthusiastically embraced by most Amish and has largely ended a situation in which some parents felt it necessary to leave the community to care properly for their children, which normally might result in being shunned.

There is an increasing consciousness among the Amish of the advantages of exogamy. A common bloodline in one community will often be absent in another, and genetic disorders can be avoided by choosing spouses from unrelated communities.

Amish do not carry private commercial health insurance. The Amish of Lancaster County, however, do have their own informal self-insured health plan, called Church Aid, which helps members with catastrophic medical expense. About two-thirds of the Amish there enroll.[10]

Most Amish do not practice any form of birth control. Suicide rates for the Amish of Lancaster County were 5.5 per 100,000 in 1980, compared to overall rate in the U.S.A. of 12.5 per 100,000.[11]

Education

The Amish do not educate their children past the eighth grade, believing that the basic knowledge offered to that point is sufficient to prepare one for the Amish lifestyle. Almost no Amish go to high school, much less to college. In many communities, the Amish operate their own schools, typically one-room schoolhouses with teachers from the Amish community. These schools provide education in many crafts, and therefore are eligible as vocational education and fulfill the nationwide requirement of education through the tenth grade or the equivalent.

In the past, there have been major conflicts between the Amish and outsiders over these matters of local schooling. One of these issues reached the U.S. Supreme Court and is considered a landmark religious freedom case. On May 19, 1972, Jonas Yoder and Wallace Miller of the Old Order Amish and Adin Yutzy of the Conservative Amish Mennonite Church were each fined $5 for refusing to send their children, aged 14 and 15, to high school. In Wisconsin v. Yoder the Wisconsin Supreme Court overturned the conviction and the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed, finding that the benefits of universal education do not justify violation of the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment.

Since then, educational authorities usually allow the Amish to educate their children in their own ways. Issues still exist over the state-mandated minimum age for discontinuing schooling. This is often handled by having the children repeat eighth grade until they are old enough to leave school. However, when comparing standardized test scores of Amish students, the Amish have performed above the national average for rural public school pupils in spelling, usage of words and in arithmetic. They performed below the national average, however, in vocabulary.[4]

Relations with the outside world

The Amish as a whole feel the pressures of the modern world. Child labor laws, for example, are seen as seriously threatening their long-established ways of life. Amish children are taught at an early age to work hard. Amish parents will supervise the children in new tasks to ensure that they learn to do them effectively and safely. The modern child labor laws conflict with allowing the Amish parents to decide whether their children are competent in hazardous tasks.

Contrary to popular belief, some of the Amish vote, and they have been courted by national parties as potentially crucial swing-constituencies: their pacifism and social conscience cause some of them to be drawn to left-of-center politics, while their generally conservative outlook on moral and economic issues causes others to favor the right wing. They are nonresistant and rarely defend themselves physically or even in court; in wartime, they take conscientious objector status; their own folk-history contains tales of heroic nonresistance.

The Amish rely on their church and community for support, and thus reject the concept of insurance. An example of such support is barn raising, in which the entire community gathers together to build a barn in a single day. It means coming together to celebrate with family and friends.

In 1961, the United States Internal Revenue Service announced that since the Amish refuse United States Social Security benefits and have a religious objection to insurance, they need not pay Social Security taxes. In 1965, this policy was codified into law.

The Amish have, on occasion, encountered discrimination and hostility from their neighbors. During the World Wars, Amish nonresistance sparked many incidents of harassment, and young Amish men forcibly inducted into the services were subjected to various forms of ill-treatment. In the present day, anti-Amish sentiment has taken the form of pelting the horse-drawn carriages used by the Amish with stones or similar objects as the carriages pass along a road, most commonly at night.

On the morning of Monday, October 2, 2006, a gunman took hostages at West Nickel Mines School, a one-room Amish schoolhouse in Nickel Mines, a village in Bart Township of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. The gunman, Charles Carl Roberts IV, a 32-year-old milk-tank truck driver who lived nearby, eventually killed five girls (aged 7–13) and then himself. The incident shocked the entire nation still grieving over two other shooting incidents within that same week at public schools elsewhere across the nation.

Asked by a reporter if the community was angry about the killings, one Amish grandmother, Lizzie Fisher, was adamant. "Oh, no, no, definitely not," she said. "People don't feel that around here. We just don't."

Notes

- ↑ The Amish Population in 2021 Amish America, August 12, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ↑ Amish Population Change, 2000-2021 Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies, Elizabethtown College. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ↑ S. M. Nolt, A History of the Amish (Intercourse, PA: Good Books2003. ISBN 9781561483938).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 John A. Hostetler, Amish Society (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993, ISBN 9780801844423).

- ↑ Donald B. Kraybill, The Riddle of Amish Culture (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001, ISBN 9780801867729).

- ↑ Tom Shachtman, Rumspringa: To Be or Not to Be Amish (New York: North Point Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0865477421).

- ↑ Beth Rice, https://www.dutchcrafters.com/blog/amish-wedding-traditions Dutch Crafters, February 2, 2019. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ↑ Donald B. Kraybill and Steven M. Nolt, Amish Enterprise: From Plows to Profits (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1969, ISBN 9780801878053).

- ↑ Howard Rheingold, Cell Phone use by Amish Wired, January 1, 1999. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ↑ Michael Rubinkam, Amish Reluctantly Accept Donations The Washington Post, October 5, 2006. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ↑ Donald B. Kraybill, John A. Hostetler, and D.G. Shaw, Suicide Patterns in a Religious Subculture: The Old Order Amish International Journal of Moral and Social Studies 1 (Autumn 1986). Retrieved June 2, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Die Botschaft. (Lancaster, PA 17608-0807). Magazine for Old Order Amish published by non-Amish.

- The Budget. (P.O. Box 249, Sugarcreek, OH 44681). Weekly newspaper by and for the Amish.

- DeWalt, Mark W. Amish Education in the United States and Canada. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education, 2006. ISBN 978-1578864478

- Garret, Ottie A. True Stories of the X-Amish: Banned, Excommunicated and Shunned. Neu Leben, 1998. ISBN 9780966793109

- Garrett, Ruth Irene. Crossing Over: One Woman's Escape from Amish Life. New York: HarperOne, 2003. ISBN 9780060529925

- Hostetler, John A. (ed.). Amish Roots: A Treasury of History, Wisdom, and Lore. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0801844027

- Hostetler, John A. Amish Society, 4th ed., Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993. ISBN 9780801844423

- Igou, Brad. The Amish in Their Own Words: Amish Writings from 25 Years of Family Life. Scottsdale, PA: Herald Press, 1999. ISBN 9780836191233

- Keim, Albert. Compulsory Education and the Amish: The Right Not to be Modern. Boston: Beacon Press, 1975. ISBN 9780807005002

- Kraybill, Donald B. The Riddle of Amish Culture. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; Rev. ed., 2001. ISBN 9780801867729

- Kraybill, Donald B. The Amish and the State, Foreword by Martin E. Marty. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2nd ed., 2003. ISBN 9780801872365

- Kraybill, Donald B. and Marc A. Olshan (ed.) The Amish Struggle with Modernity. University Press of New England, 1994. ISBN 978-0874516845

- Kraybill, Donald B. and Carl D. Bowman. On the Backroad to Heaven: Old Order Hutterites, Mennonites, Amish, and Brethren. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001. ISBN 9780801865657

- Kraybill, Donald B. and Steven M. Nolt. Amish Enterprise: From Plows to Profits, 2nd ed., Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1969. ISBN 9780801878053

- Nolt, Steven M. A History of the Amish, Rev. and updated ed., Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 2003. ISBN 9781561483938

- Schachtman, Tom. Rumspringa: To Be or Not to Be Amish. New York: North Point Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0865477421

- Schlabach, Theron F. Peace, Faith, Nation: Mennonites and Amish in Nineteenth-Century America. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2007. ISBN 978-1556351976

- Weaver-Zercher, David. The Amish in the American Imagination. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001. ISBN 9780801866814

External links

All links retrieved July 25, 2023.

- Old Order Amish Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online.

- Amish Beliefs and Practices Learn Religions.

- Amish links

- Amish Country News

- Amish Countries and Their Cultures.

- The Gentle People article about how incest is handled in the Amish community, Legal affairs.

- The Amish Get Wired—The Amish? by Paul Levinson in Wired.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.